Championing Open Science with the “World’s Largest Citizen Microbiome Project”

By Greg Watry

“There are two main benefits from crowdsourcing,” said Professor Jonathan Eisen, Department of Evolution and Ecology at UC Davis. “One, you get access to more samples at a much lower cost and much faster than you could obtain in a traditional clinical study, and two, you engage the public in the scientific enterprise.”

Eisen is a member of the American Gut Consortium, a group of scientists jointly listed as a co-author of the study.

“This is an ‘open science’ project where the data and methods and tools are being shared broadly and openly with the community,” he said. “I am very happy that the paper ended up being published in an open-access journal and thus is openly and freely available.”

Trends in the gut

The purpose of the American Gut Project, which was launched in 2012, is to establish connections between the human microbiome and health. To accomplish that, widespread collaboration is required. The open science approach allows scientists from anywhere in the world to sift through and find trends in the publicly available data.

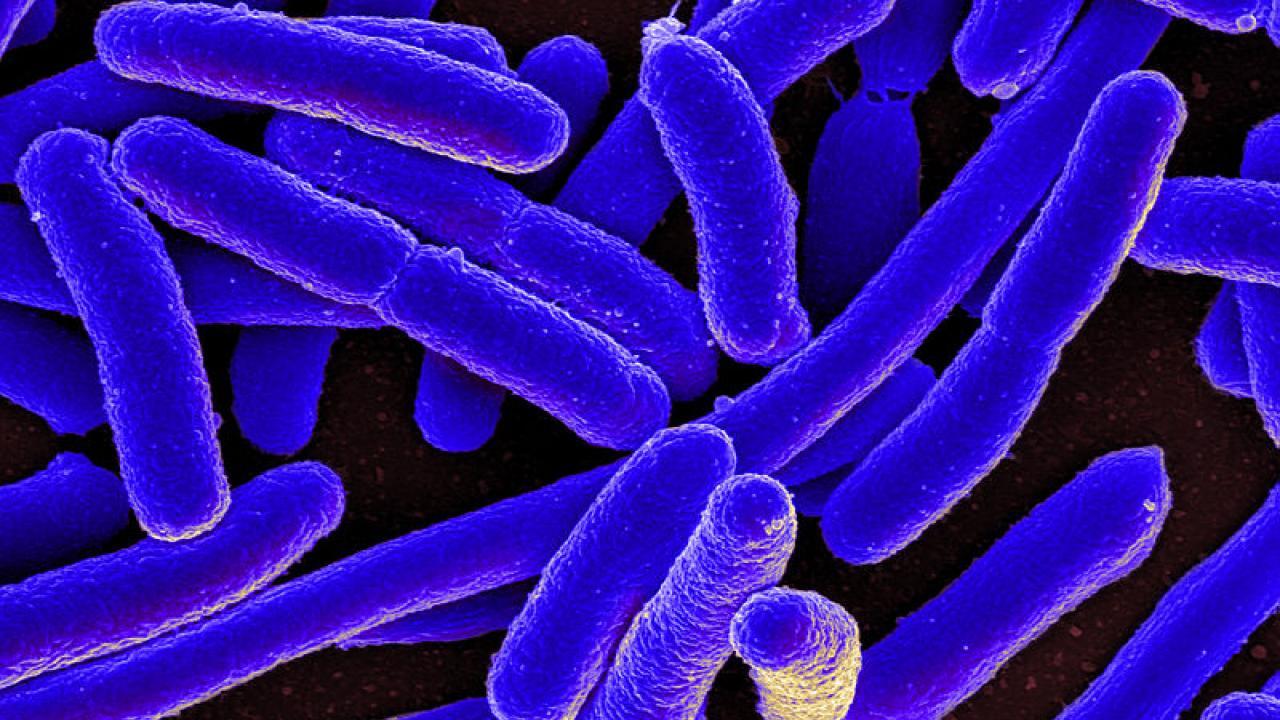

In the study, authors compared and contrasted specimens (mostly fecal samples) collected primarily from participants in the United States, United Kingdom and Australia. The authors used a variety of techniques to characterize the microbes and chemical composition of the samples. For example, the types of bacteria and archaea present in the samples was assessed using the sequencing and analysis of 16S rRNA genes which act “as a sort-of barcode for these microbes,” according to UC San Diego.

Some noteworthy trends the authors found include the following:

- More plants means more microbial diversity. Study participants who consumed 30 different types of plants per week possessed gut microbiomes that boasted greater diversity than those who ate 10 or fewer plants per week.

- More antibiotics means less microbial diversity. Participants who reported taking antibiotics in the past month possessed less diversity in their gut microbiomes than those who hadn’t taken antibiotics in the last year.

- Similarities were found in the gut microbiomes of those with mental health disorders. Participants with mental health disorders, such as depression, schizophrenia, posttraumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder possessed similar bacteria in their gut microbiomes. Similarities in the gut microbiomes of people with depression were also found.

Eisen, who was excited to just have a peripheral role in the project as a member of the American Gut Consortium, called the study a “tour de force by the main authors.”

Submitting your microbiome

The American Gut Project is ongoing, and its success is predicated on the participation of citizen scientists. Participants contribute $99 to the project and receive a mail-in kit for sample collection. Samples are then sent to either the Knight Lab at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, the Department of Twins Research at King’s College or the Australian Centre for Ecogenomics at the University of Queensland.

The American Gut Project was founded by Rob Knight, of UC San Diego, Jeff Leach, of the Human Food Project and Jack Gilbert, of the University of Chicago.

For more information on the new study, read “Big Data Dump from World’s Largest Citizen Science Microbiome Project Serves Food for Thought.”

To get involved and learn more about the American Gut Project, visit www.americangut.org

Original article at College of Biological Sciences.

Comments